Hyousatsu: Why do Japanese people typically post nameplates in front of their houses?

In Japan, there’s something called a “Hyousatsu.” It’s like a nameplate that you can find at the entrance of a house or in the reception area, which is also known as the “Genkan.” This nameplate usually shows the last name of the family living in the house. Sometimes, it might even have the names of other family members.

What is Hyousatsu?

Hyousatsu is a special nameplate that you can find in front of Japanese houses. It’s like a sign that tells everyone who lives in the house. Usually, it shows the last name of the family, and sometimes, it also includes the names of other family members. This nameplate helps people, like the mailman, to know exactly where to deliver letters.

The Hyousatsu is important because it helps people know who lives in the house. It’s especially useful for the mail carrier. They can look at the Hyousatsu, find out the family’s name, and make sure the mail goes to the right place.

But the Hyousatsu is more than just a helpful sign. It also shows the family’s status. That’s why families in Japan put a lot of thought into their Hyousatsu. They want it to represent them well. So, they take great care in designing it. It’s a small detail, but it tells a big story about the family living inside the house.

In the past, these nameplates, or “Hyousatsu,” were made of wood. The family’s name was written in a special way – from top to bottom, just like how they write in Japan. But things have changed a lot now.

History of Hyousatsu

This nameplate, has a long history in Japan. It first appeared during the Edo era, from 1603 to 1868. But back then, it wasn’t very common. Only Samurai houses had them. This was because most people, like farmers, artisans, and merchants, only had first names. They didn’t have official last names unless they paid money to the local lord.

People in the Edo era usually stayed in one place for a long time. They didn’t move around much. So, just knowing someone’s name was enough. In places like hostels, there was a list of everyone who lived there on the door. The landlord and the people living there were like one big family. So, even without a nameplate, they could find each other.

But things changed in 1872. A new law called the Household Registration Law was passed. Now, everyone, not just Samurai, had last names. Also, the postal system was set up. Mail was sent to an address and a name. So, nameplates started to be used to show who lived in a house.

During the Taisho period, from 1912 to 1926, Japan’s economy grew a lot. There were new trains and highways. The postal system also got stricter about addresses. If more than one person had the same address, the mail carrier had to knock on doors. So, people started putting nameplace in front of their houses. It made it easier for the mail carrier to deliver mail.

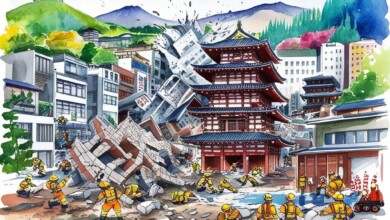

Then, after the Great Kanto Earthquake on September 1, 1923, Hyousatsu became even more popular. They helped people figure out who was still living in a house and who had moved because of the earthquake damage.

Superstitious notions concerning

A “Hyousatsu” is more than just a nameplate in Japan. It also shows how important a family is. For example, big companies like Itochu Corporation have their founder’s last name on their Hyousatsu.

Many people in Japan believe that the material of the Hyousatsu can bring good luck to the family. The two luckiest materials are Hinoki wood from the Pine family and stainless steel. Hinoki wood stands for youth and spring, full of energy. Stainless steel is known for its strength.

The color, writing, and where the Hyousatsu is hung can also bring good luck. Wooden Hyousatsu are best for traditional houses. Most Hyousatsu are hung a little higher than eye level to follow feng shui rules. They usually have black writing in clear strokes to attract wealth.

Hyousatsu is also related with two more superstitious ideas. In the book “Strange Customs of Japan” (日本のヘンな風習), the Japanese also have a custom to hang monkey masks next to Hyousatsu to pray for passing the exam successfully, just like monkeys never fall from the sky tree.

In Japan, stealing Hyousatsu is one of the techniques to pray for passing the exam. Accordingly, the Japanese think that if you steal 4 name plates from 4 different households, you will master the exam, which derives from the pun “4軒盗る – Shiken toru” (stealing from 4 houses) (stealing from 4 houses). Similar to “試験通る- Shiken tooru – Pass the exam.” After passing the exam, the student will return to the residences where he took the Hyousatsu to lay the letter and thank you present in front of the Genkan.

In the memoirs of novelist Ibuse Masuji, he once remarked that he too had his house nameplate stolen, and had to eventually adapt to paper nameplates. Or Ishida Kazuo, the ninth-dan Shogi chess player, had Hyousatsu stolen during the student test season.

Is it required to hang Hyousatsu in front of the house?

There is no questioning the benefits that Hyousatsu delivers, such as making it convenient to receive correspondence, without causing misunderstanding, developing confidence with neighbors and especially people will remember you for prompt support if calamity comes.

However, with nameplate, strangers might readily discover your home address, placing you in danger if you are taken advantage of by crooks, especially women who live alone.

To prevent hazards, many Japanese people have chosen to cover their names with Latin characters rather than Kanji on their nameplates. After all, the decision whether to install nameplate at the front door is not necessary in Japan at all but relies on the family.